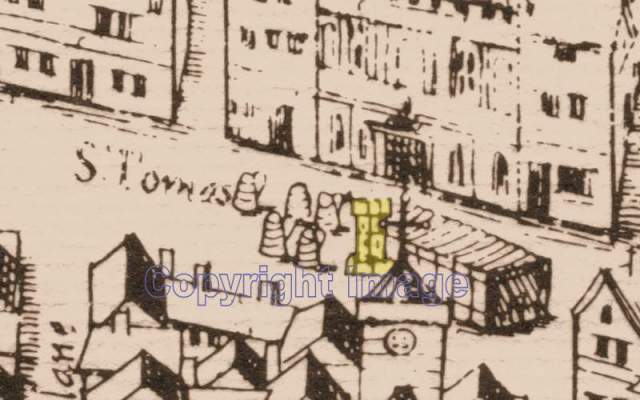

Above: An enlargement of a small part of the ‘Copper Engraving’ made about 1555. It shows the Great Conduit (shaded yellow). The view is slightly obscured by the large weather-vane on a nearby church which is drawn to the immediate right of the conduit. To the left are shown five large water jugs made of thick leather which could be filled from the conduit and then used to pour water into other vessels owned by the house-holders. The large ‘shed’ to the right represents market stalls, in the middle of the street. Behind the conduit, on the north side of Poultry (at that time), the Mercers’ Chapel is shown.

Conduits are one of the subjects of medieval London that are seldom talked about. By the 13th century there were so many people living in the City of London that water supplies, provided by wells and water pumps in many streets, could not keep pace with the needs of the population. A revolutionary idea was put into practice in the 13th century by bringing fresh water from a spring, in what was then open countryside near today’s Marble Arch, via a large pipe, across the land to a suitable point on a main street in the City.

The pipe was called a ‘conduit’, derived from a Latin word meaning ‘to lead’ – in this case to lead the water to the required location. Although it was the pipe that was actually known as the ‘conduit’, the structure supporting the water tap at the end of the long pipe also became known by the same name.

As time went by, several conduits were constructed but our story is all about the first one which became known as the Great Conduit.

What was remarkable about each project was that the pipe had to carry the water for a distance of two miles – or more. The entire length of the ‘pipe’ was gravity fed. The ‘pipe’ was made up from tree trunks, each one about 10 to 20 feet long, bored through the centre with a six-inch auger. Each section then had to be connected to the next by shaping the ends to form a joint that leaked as little water as possible. Today we could easily complete the project by using plastic pipes and, if they leaked, we could use mastic to seal the joint. The sheer effort that went into constructing a long conduit in medieval times was nothing short of amazing!

The first conduit to be laid in London was the so-called ‘Great Conduit’ which was begun in 1238 but not completed until 1245. Water was conveyed 2.7 miles (4.3 km) from Tyburn (from a spring just north of Oxford Street) all the way to Poultry. Its route was via today’s Constitution Hill; the Mews at Charing Cross; Leicester Fields (now Leicester Square); along Strand and Fleet Street; via Cheapside; and finally to Poultry.

When fully working, the tap was under the care of a keeper who locked it up and only allowed water to be drawn in his presence.

In the 1270s, when Edward I brought his wife to London for the first time, the conduit ran with wine. About a decade after that time, the conduit was rebuilt.

It was destroyed in 1666, in the flames of the Great Fire and not rebuilt because it was in the way of the traffic.

Its exact site was lost for several centuries until the 1990s when workmen completing the exterior of One Poultry found evidence of the Great Conduit under the pavement of Poultry, on the souther side.

Its site was described as being ‘at the eastern end of Cheapside, in the middle of the street, opposite the Mercers’ Chapel, near the end of Old Jewry.’ Today we can describe the site as being ‘in front of Tesco Metro.’

Above: The plaque, set into the pavement on the south side of Poultry. (There is a larger version of the inscription on the image below).

I have known about the Great Conduit and knew roughly where its had stood but it was only a few days ago that I was walking along Poultry and noticed that a special plaque had been placed in the pavement, on the south side, to mark the exact spot.

Above: The plaque states ‘The Great Conduit lies beneath this spot. Built by the City of London in 1245 to provide public water water supplied by pipe from Tyburn springs. Removed after the Great Fire in 1666 and found during the construction of One Poultry in 1994.’

It would appear that the plaque in the pavement has been there since 1994 and I had only just noticed it in November 2014! It is surprising what we all walk past every day and never notice!

-ENDS-

Thank you for sharing this! I personally have some family history with the conduit and have wanted to travel and visit the spot. You’ve brought it to me! Thank you for the great pictures and information on the water’s travel and history!

LikeLike

It is interesting for me to have a written a blog that relates directly to you family history.

LikeLike

Where can you see the engraving which shows the image of the conduit?

LikeLike

Under normal circumstances, you could see the Copper Engraving in the Museum of London. They are currently closed as is the case with all other museums in London.

LikeLike

Amaze! Thank you! I constantly wished to produce in my internet site a thing like that. Can I take element of the publish to my blog?

LikeLike

Thank you for your enthusiastic comment. As you can see the photo is copyright and the text in my article is also copyright. Sorry.

LikeLike

I am doing research for a story based around water supply in London and came across your very interesting article. My primary investigative goal is to find out if a device as described below was used in Medieval times as a means to pump water from its source for use either by households or industry. My description is – a round container perhaps similar to a well that had a “Cramk” device which would be pushed manually by a person in a rotating direction to pump the water to the surface” I live in young Australia without your valuable and informative history. I am hoping even for a glimmer of fact that may lead me in the direction I need to go. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you for your interest. I have not researched all the possible ways that medieval Londoners were supplied with water but I do know most of the places where they had access to water supplies. Some of them were wells, some were water pumps where the user had a handle to pump the water from what had previously been a well. Another option was a conduit, so-called because water was conveyed by large wooden pipes from a spring. Those springs were sometimes as much as three miles away from the water tap (also known as a ‘boss’ or ‘standard’). Sorry I cannot be of more help. I do not recognise the description that you have given.

LikeLike

Can you tell me if the (modern) water feature on the corner of Foster Lane and Cheapside is a response to/ commemoration of some kind of water source here? Thank you!

LikeLike

It is an interesting idea but I don’t think so. It was built (as far as I know) by the people who created the new offices on the curved corner. They are a very uncommunicative lot at the offices. I tried to get in touch when they opened about 10 years ago but I could not find anyone to reply to my queries. One of the conduits was very close by but I do not think that has anything to do with the new water feature.

LikeLike

Thanks Adrian- you aroused my curiosity and I did a bit of digging. The one very close by you refer to must be the one on the opposite side of Cheapside, actually almost opposite Foster Lane.

LikeLike

Yes, the link you have enclosed is to a Website that has ripped off most of the information in one of my publications (without even a name recognition). That’s how the world works, unfortunately. Don’t trust their map too much. They made several copying errors.

LikeLike

Sorry about that! What is your publication?

LikeLike

A-Z of Elizabethan London.

LikeLike